At times of crisis, illness, and despair, our faith in God comes clearly into focus. Whether one is deeply religious or not, being a part of a community interlaced with faith, belief, and prayer can console us and give us strength and hope.

But what about those who don’t believe in a God and reject the teachings of religions and scriptures? How do non-believers navigate the injustices and cruelties of the world, and to whom do they pray when they need to be heard?

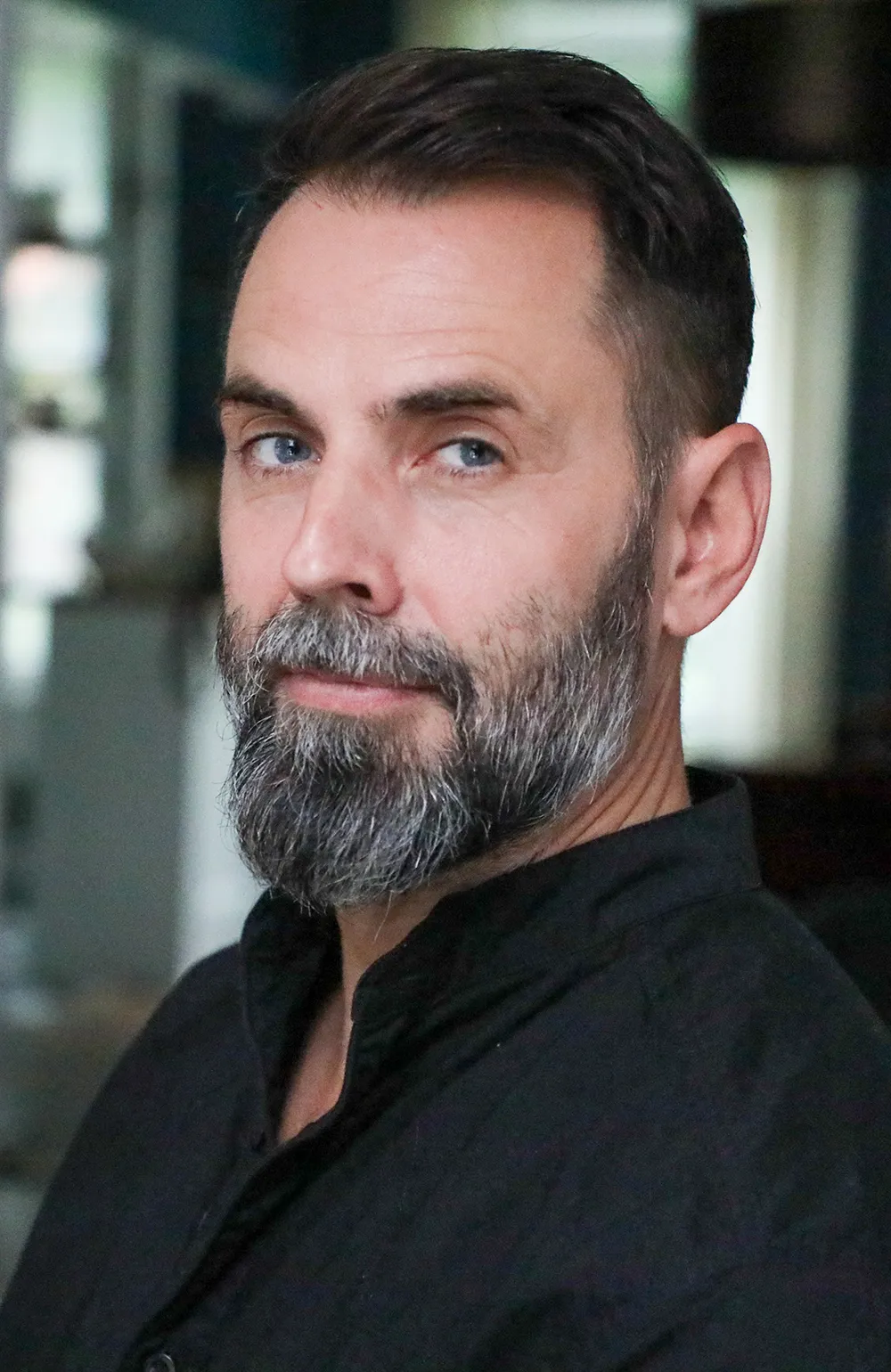

For humanist Chaplain Devin Moss — writer and host of The Adventures of Memento Mori podcast — wrestling with these concepts is part of his day-to-day job, and he’s okay with that. Although Moss doesn’t believe in a God, he acknowledges something spiritual in all of us and in the goodness of mankind — often in the face of compelling evidence to the contrary.

“Christianity and its form that was presented to me did not settle with what I was looking for,” says Moss. “I did have an inherent sense of spirituality, it felt like there was something more … there's something there in the center of us.”

Moss’s interest in humanism and his experience as a chaplain providing spiritual care at Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan led him to his toughest challenge to date: a year-long bond with inmate Phillip Hancock. Chronicled recently by the New York Times, Hancock was sitting on death row at the “Big Mac” State Penitentiary in McAlester, Oklahoma, convicted and sentenced to death for double murder.

“His attorney team reached out to the American Humanist Association because he was looking for a non-theist chaplain,” Moss says. “[Hancock] didn't want to proselytism, the goal wasn't to save his soul, but he did want spiritual care.”

Though Moss frequently questioned his own abilities during that time, saying he was “wildly insecure” about whether he was actually helping Hancock, his compassion was steadfast. Ultimately, clemency for Hancock was denied by the Governor of Oklahoma, and Moss remained by his side in the days, hours, and minutes before his execution.

“One of the things that really sticks with me the most is that Wednesday, between the hours of five and seven, is when he would get his last meal. And all we really talked about was how much he was looking forward to this big bucket of dark, original recipe Kentucky Fried Chicken,” Moss recalls. “And instead of giving him what he had asked for, they gave him a ten-piece chicken strip that was dried out, just to mess up his last meal. [It’s] so heartbreaking because it doesn't take much to display thoughtfulness.”

Early on in their journey, Moss had asked Hancock what he wanted from him. Hancock referred to Philippians 4:7-8, which he interpreted as “show me something real, show me something true.” Upon entering the execution chamber, Moss recited these lines:

“I call the spirit of humanity into the space that love fill our hearts. We ask that in this transition into peaceful oblivion, that Phil feels that love, and although that this is his journey, that he is not alone. We invoke the power of peace, strength, grace, and surrender. Amen.”

“I do believe that in all of us, there is the potential to be and do good beyond ourselves,” says Moss. “And Phil believes that it's all made up and that there is no such thing as inherent good or evil, so we just have to make meaning, and that leads to amazing existential conversations.” Photo credit: Marie-Helene Carleton.

Delve deeper into life, philosophy, and what makes us human by joining the Life Examined discussion group on Facebook.